Murnau and up to the present day not only the look but the inherent nature of Dracula has been transformed. From his initial transfer from the page and first appearance in the early stage productions of Hamilton Dean and his first tentative steps in front of the camera of F.W. Some of these changes have been so dramatic and so fundamental to his nature that the Vampire King we see today is virtually unrecognisable to the one created by Stoker over a hundred years ago. This paper aims to look at the ways the immortal Count has changed not just across mediums but because of the inherent nature of those mediums themselves. However, whilst remaining fixed on the page, he has evolved almost beyond recognition in its adaptations on stage and screen. Since its publication in 1897 Bram Stokers Dracula has never been out of print, a reflection of the immortality of the undead Count himself. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust.

It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films.

I conclude that the synergy of the literary gothic, stage melodrama, and Expressionism that characterises Gothic film now finds its purest form in the films of Tim Burton and Guillermo del Toro. The paper also considers period revivals such as Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein by Kenneth Branagh (1994), as well as more contemporary Gothic film, in particular the current trend for franchised vampires.

Murnau’s Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922), and James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

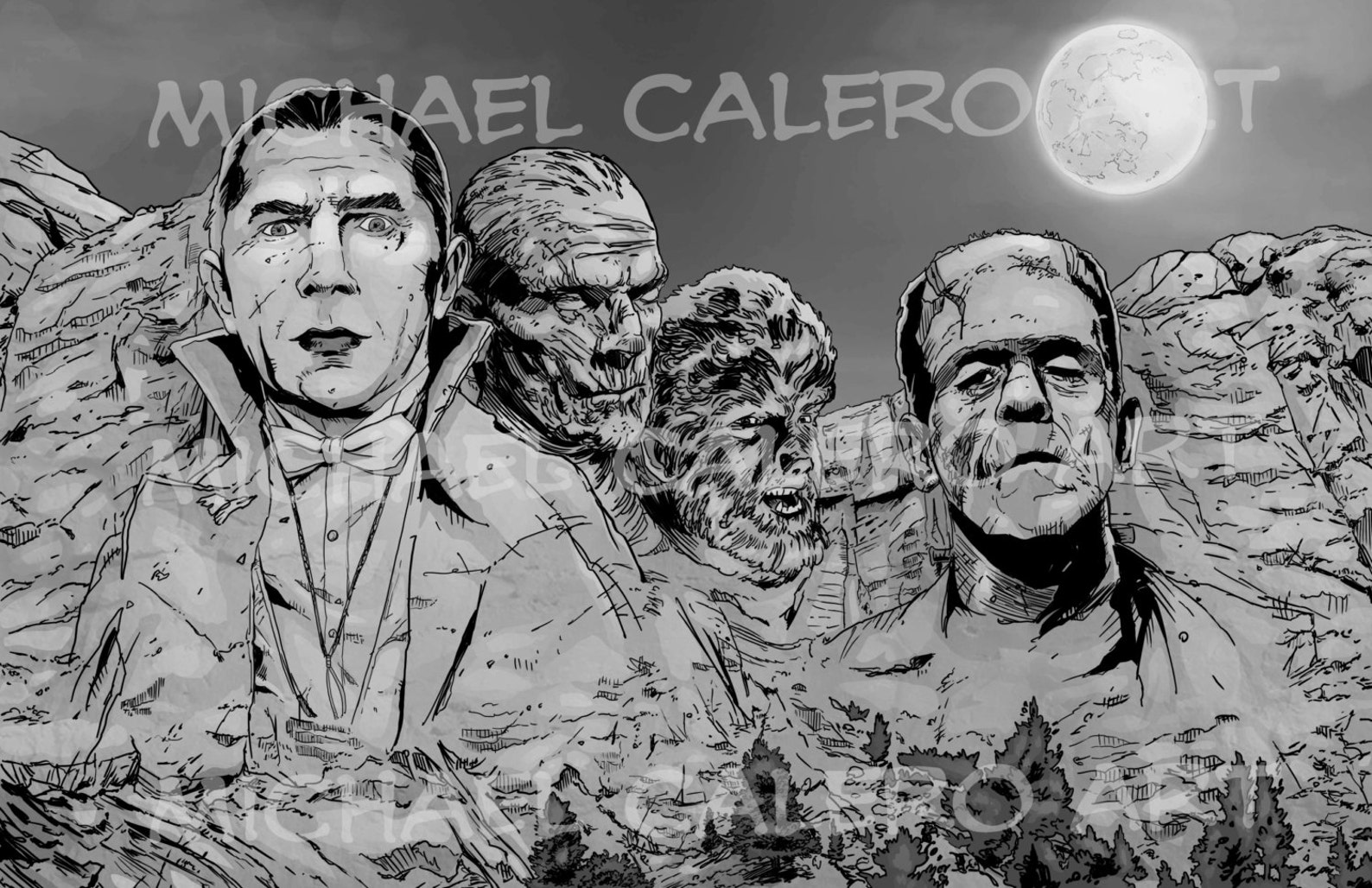

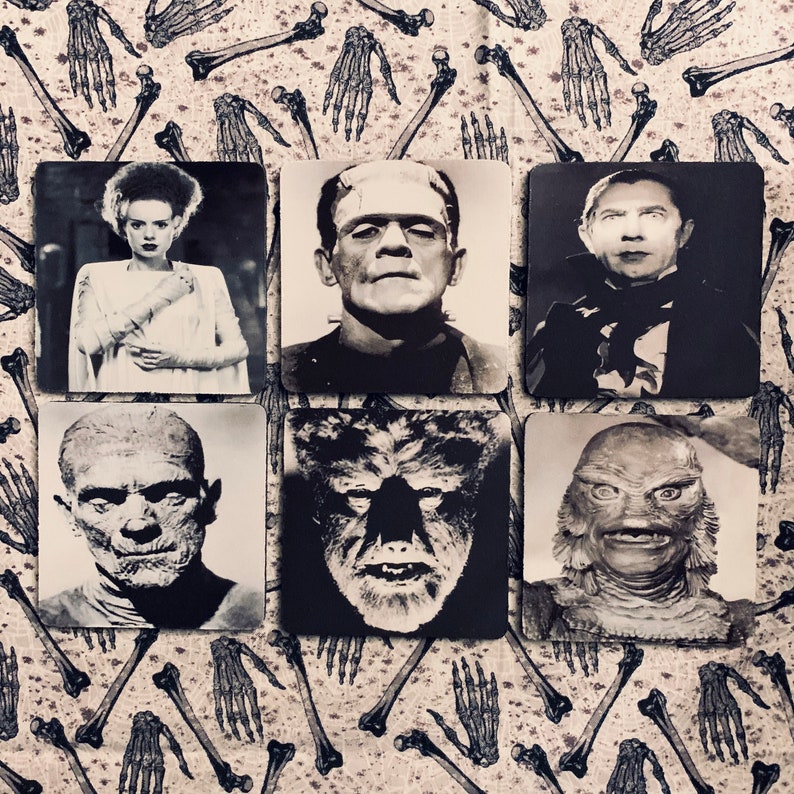

#FOLDING PAPER MONSTERS DRACULA MUMMY WOLFMAN FRANKENSTEIN FULL#

The full entry includes close readings of Robert Weine’s influential and often imitated Das Cabinet des Dr. Ainsworth Thomas De Quincey John Polidori Regency Tales of Terror Monster Movies Richard Matheson.) This is an historical overview of the form from early European and American silent adaptations of Gothic novels and Victorian theatre to the hyper-real twenty-first century Hollywood product, via Expressionism, Universal Studios, Hammer Films, Mario Bava, and Roger Corman’s ‘Poe Cycle’ for American International. (Other entries: David Cronenberg Hammer Films W.H. Smith eds, Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Gothic 2 vols.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)